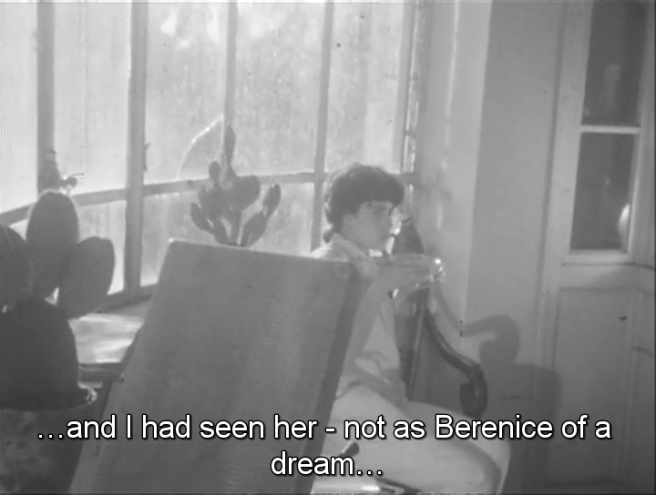

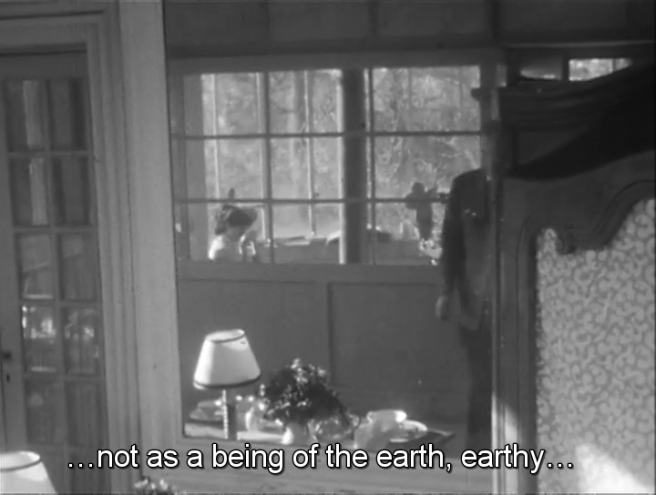

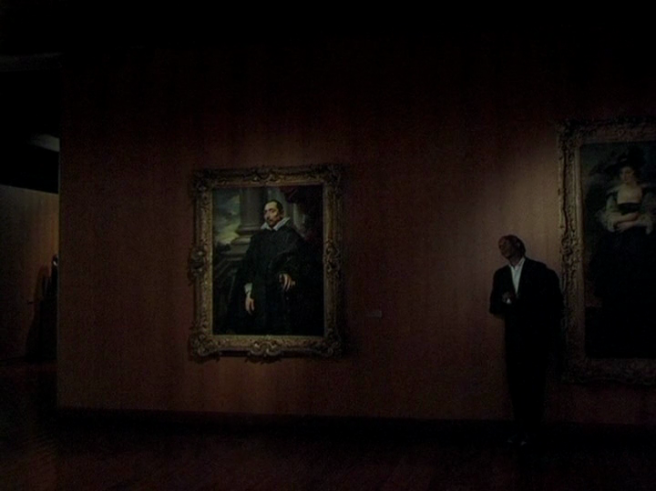

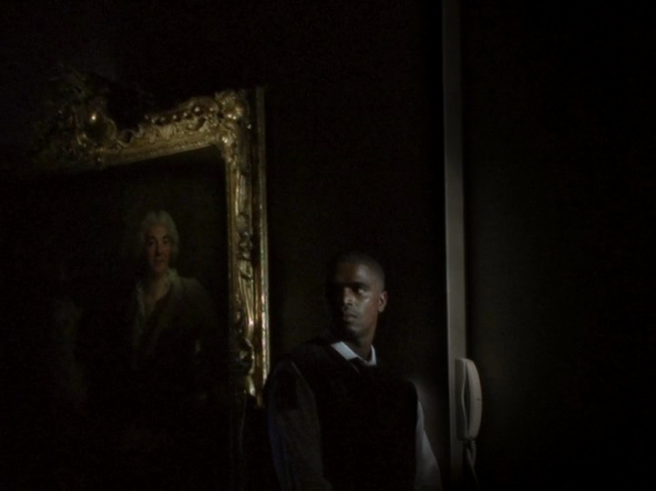

Even Godard’s detractors must admit that he’s an astounding image maker. Godard has a way of filming people that cuts directly into their emotions. He sees through people, through their features and into their psychology. Godard’s ability to create spontaneous images of classical beauty is unsurpassed in cinema.

Even Godard’s detractors must admit that he’s an astounding image maker. Godard has a way of filming people that cuts directly into their emotions. He sees through people, through their features and into their psychology. Godard’s ability to create spontaneous images of classical beauty is unsurpassed in cinema.

Note, I feel remiss talking about Godard’s images here without mentioning his sounds. While this is difficult to represent here, it’s crucial to the success of his films. Godard’s use of sound borders on the Eisensteinian idea of sound and image as disconnected, separate forces that form a cohesive but not direct whole.

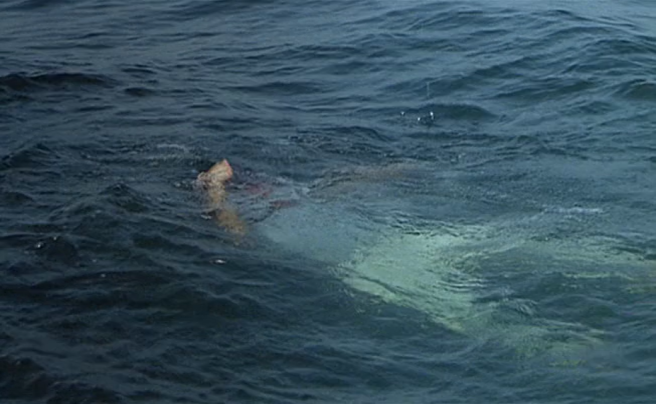

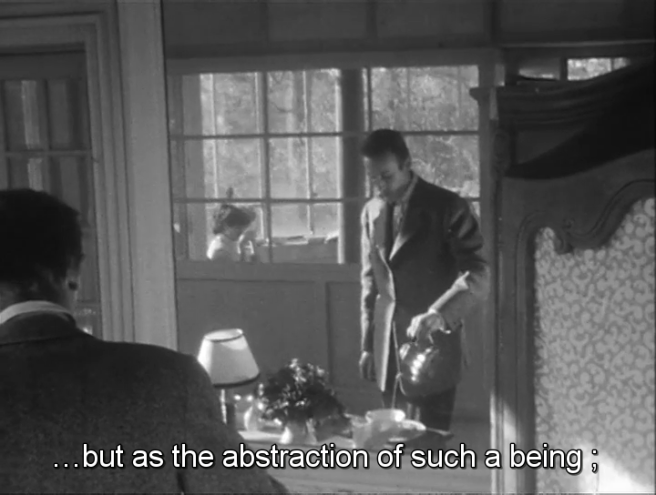

Nouvelle Vague (1990) by Jean-Luc Godard

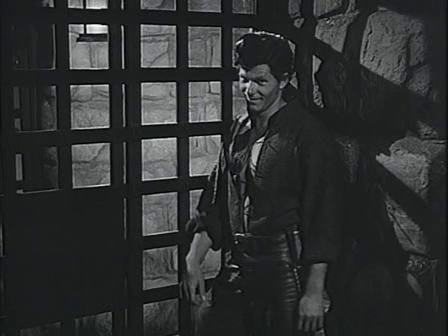

Ford’s myths as dances of images.

Ford’s myths as dances of images.